Buzzfeed published an article last week largely based on a study conducted by Adthena, a paid search competitive intelligence company. The main point of the story was that Amazon engaged in a targeted strategy to aggressively bid on competitors’ branded terms over the Black Friday to Cyber Monday period.

We found the article and the supporting research to be misleading. Nothing in either piece supports the point of view that Amazon was doing anything intentionally aggressive or even differentiated. The purpose of this blog post is to provide more context as well as correct information on competitive brand bidding and Google’s trademark policy itself.

Misleading metric

The central data point of the article and the Adthena report was that “Amazon's brand bidding rate over Black Friday weekend came to 182.18%, meaning an Amazon ad was 1.8 times more likely to appear on a competitor's brand term — Wayfair, Walmart, Macy's — than in searches for Amazon itself.”

This metric, however, is a poor way to evaluate competitive brand bidding and is intentionally misleading. It is meant to make the uninformed reader think there is something differentiated and aggressive with Amazon’s paid search strategy.

Let’s look at the the metric itself. The numerator is the number of times that Amazon ads appear on searches for brand terms that are viewed to be competitive. If Amazon appears on lots of competitors’ brand terms the metric could be high. We’ll discuss later why this is unlikely, in Amazon’s case, to be a meaningful signal.

The denominator in the metric is the number of times that Amazon advertises on its own brand terms. If Amazon does very little advertising on its brand, then the metric can appear very large. As it turns out, Amazon generally doesn’t advertise on its own terms on desktop search. It doesn’t need to.

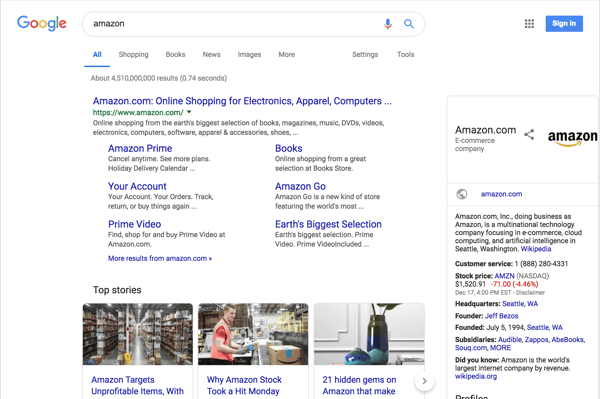

With more and more consumers starting their shopping journey on Amazon’s site, an Amazon ad on Google is unlikely to add new Amazon users. Here is an example of the Search Engine Results Page for "Amazon" searched from New York city.

As you can see, there is no Amazon ad, but also 100% of the real estate sends users to Amazon itself.

Competitive brand bidding defined

Competitive brand bidding is usually an intentional effort by the brand to display their ad on a competitor’s search term. There are two main types of competitive brand bidding: an ad where a brand bids on a competitor’s branded terms and says “shop here instead” and an ad where a brand compares itself to the competition and says “we are better” in some way. When someone uses the phrase “competitive brand bidding,” industry experts typically think of these two types.

The Sears and Williams Sonoma ads featured in the article as examples of competitive brand bidding, wouldn’t typically be considered such by industry experts.

In the Sears ad, pictured below, Amazon doesn’t even appear to be targeting Sears. What the Amazon ad shows, which features a misspelling of Sears, is more likely a poorly chosen keyword strategy–not a competitive bid to win strategy on Sears’ keywords.

In the Williams Sonoma example, shown below, Amazon is promoting and linking to books published by Williams Sonoma, not a general page with cooking products. In this case, Amazon is a sales channel for Williams Sonoma books, not a competitive brand bidder.

Amazon sells many products from a variety of brands and it bids aggressively for the brands it sells. The vast majority of the time, when they brand bid, they are also selling items from those brands on their site, which paid search experts wouldn’t consider competitive brand bidding.

Amazon sells many products from a variety of brands and it bids aggressively for the brands it sells. The vast majority of the time, when they brand bid, they are also selling items from those brands on their site, which paid search experts wouldn’t consider competitive brand bidding.

What does competitive brand bidding look like?

If the examples in the Buzzfeed article don’t meet the definition of competitive brand bidding, then what does? Competitive brand bidding is when a company like Nike bids on Adidas’ branded terms or vice versa with the intent of diverting traffic from a competitor’s site and driving it to their own site.

This type of competitive bidding usually manifests itself in two ways.

One way is when a company runs a general ad like, “Looking for Company A? We also sell [product that Company A sells].” Google allows this type of bidding. The reasoning is that these types of ads are informational and give consumers more choice.

In the example below, Bose is bidding on the term “Sonos speakers.”

Another way is when a competitor runs an ad that says “Compare us to the competition – we’re better.” This type of competitive brand bidding runs afoul of Google’s trademark rules and can be submitted for takedown. In the example below, Acuity Scheduling is clearly saying they are better choice than Calendly.

None of the Amazon ads in the article fall into either of these two categories of competitive brand bidding. Amazon for example, isn’t saying that it is better than Williams Sonoma and that the customer should buy from them instead of Williams Sonoma. Instead the ad is saying, “We have what you are looking for.”

While brands might prefer to have their customers come and buy directly from their site, with so many customers beginning their buyers journey on Amazon, it’s difficult for brands to walk away from that potential revenue. So, the brand who chooses to sell direct from their website and also on Amazon, will likely find themselves competing with Amazon for traffic.

Google trademark rules

The Buzzfeed article states, “Google lifted a ban on competitors using trademarked ad words in June 2009, bringing it in line with other search engines like Bing. That meant retailers like Best Buy, or Amazon, are free to use competitors' names in ad copy.”

What Google did, in fact, in 2009 was allow resellers and informational sites to use the trademark in the ad text, but not for competitive purposes. Amazon is one of the largest resellers in the world and as such, is allowed to bid on the trademark (and use it in the ad copy) of the brands that it sells on Amazon.

Today, Google’s trademark policy says: “We don’t investigate or restrict trademarks as keywords.” This means brands may bid on trademarked terms. The policy also says, “We may restrict the use of trademarks in ad text,” and then they go on to explain that resellers and informational sites are allowed to use trademarks in the ad text.

Google’s trademark policy, however, does not allow “ads referring to the trademark for competitive purposes.” This is why the Acuity Scheduling ad would be taken down but the Bose ad would stand.

We have written several blog posts on Google Trademark rules and commonly asked questions regarding Google’s trademark policies because we are often asked to explain these rules to our customers.

So what is interesting about the Amazon brand bidding story?

Honestly, not much. As we discussed above, the metric on which the entire story is based on, is flawed. The examples featured in the article and the Adthena report don’t meet the industry standard of competitive brand bidding. In general, we do see brands become more aggressive during Q4. Historically, there is a 20-30% increase in brand bidding around the holidays, but there was nothing particularly unique or aggressive about Amazon’s actions. We had limited monitoring (4 times a day) set up over the Black Friday-Cyber Monday weekend across 250 popular brands in 10 industries, and didn’t find any evidence to suggest that Amazon was pursuing an aggressive competitive brand bidding strategy during this time.

In conclusion, we don’t think Amazon pursued a targeted competitive brand bidding strategy over the Black Friday weekend. Amazon, which has made no secret of its ambition to sell everything, carries a lot of brands. As Amazon continues to grow its number of partners and sellers, the amount of brand bidding it will engage in, will only increase. We shouldn’t be surprised to find Amazon bidding on the keywords of the brands they carry.